First Published in Swing Time: Reginald Marsh and Thirties New York (New York Historical Society, 2013).

When I was a kid during World War II my parents would sometimes take me to Coney Island on a hot summer weekend. It was a special treat enjoyed by many others who lived in the dark, crowded tenements of the Lower East Side. For working-class families in New York in the 1940s, Coney Island was an escape from the city into sun and surf though certainly not from overcrowding. What I most recall is the almost unbelievable mass of humanity that blanketed every inch of the sand and filled the fringes of the rolling surf. To Robert Moses, New York’s imperious parks commissioner, the beach was revoltingly plebeian and not at all salubrious, reproducing the crowded conditions of the slums at the edge of the sea. And like other progressive reformers and arbiters of public morals, he despised Coney Island’s amusement parks for their peep shows, freaks, and cheap thrills, which hardly spoke to the best in human nature. Even before the subway was extended in 1920, when Coney Island remained accessible mainly by boat or trolley, it had become a vast playground for the masses. Once infamous for its gambling dens and houses of ill repute, often called a “Sodom by the sea,†it had grown far more respectable by Marsh’s time but still a saturnalia, forever lowbrow. Moses’s response was to transform a pristine stretch of land further east on Long Island into Jones Beach, a suburban state park for the burgeoning middle class, one that could be reached only by auto, not by public transportation, a park geared for families, with no sideshows or midway.

As an artist Reginald Marsh was attracted by the same features of Coney Island that repelled Robert Moses: the crowds, the sea of flesh, the blatant self-display, the blaring signage, the honky-tonk, the public spectacle. For a brief moment in the lives of those who had come to enjoy it, Coney Island’s carnival culture it set aside the work ethic and the moral censor that otherwise ruled their lives. Though politically committed artists of the 1930s dismissed Marsh’s work as a specimen of the “Coney Island School of Art,†he belonged to no school but that of his own voyeuristic curiosity and imagination. Everyone agrees that the Depression was his decade, that his art came into its own by the early 1930s but shifted dramatically after 1940, growing more nostalgic and less grounded in the thick of everyday life. Yet even during the thirties it scarcely resembles the output of any other Depression-era artist. Though he was pegged as a regionalist, his paintings, drawings, and engravings pulsate with an urban energy that contrasts sharply with the static, folksy rural imagery of thirties regionalists like Grant Wood and John Steuart Curry. And despite some arresting depictions of unemployed men and Bowery derelicts, Marsh’s work eschews the stark iconography of exploitation, protest, and victimization favored by painters like Ben Shahn and the Soyer brothers or socially conscious New Masses artists such as Hugo Gellert, William Gropper, and Anton Refregier, who were primarily political cartoonists. If Marsh was an especially linked with the artist Depression, as the calendar indicates, then his work expands our notion of Depression-era art and culture.

My first serious encounter with Marsh’s art came through work that he did after the Depression that nevertheless reflects the characteristic style he developed during that decade: his 1946 illustrations for one of the most ambitious literary works of the 1930s, John Dos Passos’s panoramic trilogy U.S.A. (1930-36). The fluent, prolific Marsh produced more than five hundred line drawings for these volumes, some 470 of which were published, and they match Dos Passos’s vision with remarkable fidelity.1 U.S.A. is famously a novel without a central plot or a single set of interacting characters. It’s braided with different narrative techniques, multiple story lines, and a mixture of social types – the proletarian drifter, the public relations man, the career woman – rather than highly individualized figures. Its elaborate montage includes subjective autobiographical passages, newsreel headlines, and miniature biographies of real people.

Marsh’s drawings, notable for their nervous, agitated lines, convey body language more than facial expressions and they faithfully reproduce the broadly generic situations in which Dos Passos’s characters find themselves. Marsh had begun work in the 1920s as an illustrator and cartoonist and his drawings for U.S.A. come close to caricature, though they avoid grotesque exaggeration. As a realist Dos Passos supplies a swift but sometimes numbing cascade of detail, as if summarizing lives rather than recreating them. Marsh, with a cartoonist’s economy, helps us visualize these characters, but he steers clear of personal traits or idiosyncratic emotions that would individualize them and give them depth. They have setbacks and successes, shifting moods but no inner lives. He boldly depicts intimate situations between men and women, as Dos Passos does, yet the lovers remain shallow, as if they had simply drifted into each others’ orbit. These anecdotal drawings, like the trilogy itself, come through as the detached work of a gifted observer recording features of the human comedy. Such an external approach is typical of artists and writers in the 1930s, who often preferred social types and their milieu to psychological depth and the nuances of individual character.

Faced with an overwhelming economic crisis that seemed to dwarf personal concerns, artists took on the role of the restless, attentive eyewitness, the camera eye that records life supposedly without intruding on it. Photographers, some of them sent by New Deal agencies, took to the road with their cameras, just as writers brought their notebooks to interview ordinary Americans. Marsh, going everywhere with his sketchbook, drawing constantly, then turning his drawings into larger, more finished work, assumed a stance that reminds us of photographers like Walker Evans or Dorothea Lange, writers like James Agee, Erskine Caldwell, or Benjamin Appel, ethnomusicologists like Charles Seeger or Alan Lomax, who all set about to document humble, quotidian features of American life that had usually fallen outside the purview of art. But Marsh’s difference matters. While the subjects of many of his contemporaries were overwhelmingly rural – the fate of sharecroppers, tenant farmers, Dust Bowl migrants – Marsh roamed New York for his material. Most strikingly, he was engrossed with what Americans did in their leisure time, and in public settings, not in their working hours or their drab, disconsolate home life.

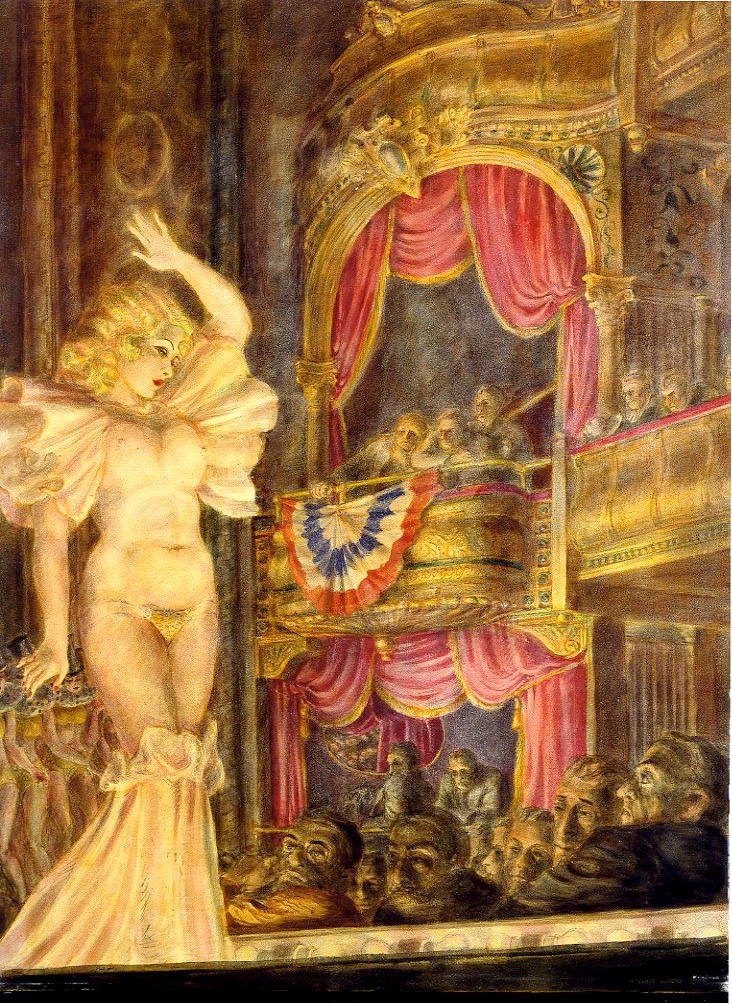

The focus on leisure rather than work, or, more specifically, on leisure as an antidote to work, almost a countervailing set of values, has a long history in modern art from the boating parties, picnickers, and ballet dancers of the Impressionists to the café and cabaret scenes of Toulouse-Lautrec and the clowns of Picasso.2 But during the 1930s such diversions could best be found depicted not in painting but played out in screwball comedies, dance films, and backstage musicals. This was the side of thirties culture usually seen as escapist fluff, designed to take people’s minds off their troubles. As the burlesque impresario Billy Minsky liked to explain the appeal of his shows during the Depression, burlesque gave people something else to think about.3 But Marsh’s innumerable images of burlesque, of Coney Island, of robust street life, demonstrate how much more was at stake in Depression-era pastimes than mere escapism. While many artists responded to the conditions of the Depression by exploring ordinary people’s troubles – the pain of being out of work, emotionally depressed, unable to feed one’s family, the trauma of being uprooted – popular entertainers were just as strongly attracted to scenes of pleasure highlighting the frivolous, the insouciant, the disreputable. To Depression audiences they represented freedom, mobility, and gratification at a time when they felt hemmed in by grievous economic troubles and limited horizons. The whole system seemed broken, the American dream betrayed, nullified. The New Deal promised recovery but it was slow in coming. At this moment the mass audience was captivated by the anarchic irreverence of the Marx Brothers, the misanthropy of W. C. Fields, the salacious doubles entendres of Mae West, along with the elegance of Cary Grant and Fred Astaire and the precocious energy and talent of Shirley Temple. They were a tonic for the glum, anxious mood of the Depression.

In her book The March of Spare Time: The Problem and Promise of Leisure in the Great Depression, Susan Currell explored the widespread pre-occupation with leisure during the 1930s, from presidential reports on social trends to the WPA construction of a gigantic network of parks, playgrounds, swimming pools, golf courses, stadiums, and athletic fields. Some of this concern about idle hours arose from the reduction of work time thanks to advances in technology, but it gained new urgency from the huge increase in unemployment due to the economic collapse. Leisure activities had long been a source of social fears about moral decline, and observers warned of “spectatoritis,†of recreations that were passive, spectatorial, therefore unhealthy, and they worried about the idleness and temptations of the wayward young, as they would again during the juvenile delinquency scare of the 1950s.4 Everywhere there was a surge of fads and crazes from miniature golf and crossword puzzles to board games, jukeboxes, and dance marathons.5 Jitterbugs developed their own youth culture around big swing bands and popular vocalists. Critics decried a shift from traditional values of work and thrift to pleasure-seeking and greater sexual liberty. They saw cheap amusements that had long been associated with the working class or with men alone becoming socially respectable. Women once confined more strictly to the home could mingle freely with men at some of these places, not in saloons or burlesque houses but at dances, movie theaters, beaches, and amusement parks, places where inhibitions were relaxed and strangers could meet.6

In her book The March of Spare Time: The Problem and Promise of Leisure in the Great Depression, Susan Currell explored the widespread pre-occupation with leisure during the 1930s, from presidential reports on social trends to the WPA construction of a gigantic network of parks, playgrounds, swimming pools, golf courses, stadiums, and athletic fields. Some of this concern about idle hours arose from the reduction of work time thanks to advances in technology, but it gained new urgency from the huge increase in unemployment due to the economic collapse. Leisure activities had long been a source of social fears about moral decline, and observers warned of “spectatoritis,†of recreations that were passive, spectatorial, therefore unhealthy, and they worried about the idleness and temptations of the wayward young, as they would again during the juvenile delinquency scare of the 1950s.4 Everywhere there was a surge of fads and crazes from miniature golf and crossword puzzles to board games, jukeboxes, and dance marathons.5 Jitterbugs developed their own youth culture around big swing bands and popular vocalists. Critics decried a shift from traditional values of work and thrift to pleasure-seeking and greater sexual liberty. They saw cheap amusements that had long been associated with the working class or with men alone becoming socially respectable. Women once confined more strictly to the home could mingle freely with men at some of these places, not in saloons or burlesque houses but at dances, movie theaters, beaches, and amusement parks, places where inhibitions were relaxed and strangers could meet.6

Marsh was irresistibly drawn to locations that troubled reformers and moralists, who set out to encourage healthier, more high-minded leisure activities, such as the parks and fields built by the WPA. By 1934, with the more draconian enforcement of censorship through the Production Code, they cracked down on the frank, freewheeling movies of the early sound era. They worked hard to ban burlesque as it turned into striptease. Marsh himself testified against the banning of burlesque at a legislative hearing in 1937, a campaign inspired by New York’s reforming mayor Fiorello LaGuardia. (The theatres were finally closed in New York in 1942 after a decade of agitation.) Like the European artists he revered, including Michelangelo and Rubens, along with American realists such as Thomas Eakins, Marsh had an endless fascination with the human body, even when it was by no means beautiful, and the beach and the burlesque house offered him unparalleled opportunities to observe in public. Like Eakins he had a rich knowledge of human anatomy and an exceptional gift for conveying its weight, mass, and sensory appeal. His lifelong friend, the art critic Lloyd Goodrich, observed that “his figures are centers of energy and movement. Even when they are clothed one feels the body beneath the clothes.â€7 Strangely, he was more engrossed by how bodies interact than how people interact, as in the crowded but impersonal beach pictures that brought back my childhood memories of Coney Island. They were evocative yet highly stylized, for he liked to depict his figures interlaced in every conceivable position, radiating not so much eros as sheer physicality. This sometimes contorted vision is more reminiscent of the writhing figures in Michelangelo’s Last Judgment than of working people enjoying an ordinary day at the beach.

Many realist artists in modern times, from Eakins to Shahn, have worked closely from photographs. For Marsh photography served as an aid to memory, complementing the sketchbooks in which he worked out both the parts and the larger design of his finished works. Yet even the paintings can feel sketched, tentative, provisional, as if to convey the instability of the image as well as the body in motion.8 His way of catching ordinary life on the fly linked him to the documentary techniques of many thirties photographers. But as Marilyn Cohen showed in Reginald Marsh’s New York, which reprints sketches and photos alongside his finished works, Marsh often fused separate images, especially of knots of people, into larger compositions that compressed the action to the point of unreality. From this baroque crowding effect, with bodies thrusting in every direction, he drew an explosive energy. Cohen observes that “what interested Marsh was not individuals in a crowd, but the crowd itself – the urban masses brought together randomly on subways, at the beaches and sideshows. Marsh detailed the world his figures inhabited, but left the inhabitants anonymous.â€9

Many realist artists in modern times, from Eakins to Shahn, have worked closely from photographs. For Marsh photography served as an aid to memory, complementing the sketchbooks in which he worked out both the parts and the larger design of his finished works. Yet even the paintings can feel sketched, tentative, provisional, as if to convey the instability of the image as well as the body in motion.8 His way of catching ordinary life on the fly linked him to the documentary techniques of many thirties photographers. But as Marilyn Cohen showed in Reginald Marsh’s New York, which reprints sketches and photos alongside his finished works, Marsh often fused separate images, especially of knots of people, into larger compositions that compressed the action to the point of unreality. From this baroque crowding effect, with bodies thrusting in every direction, he drew an explosive energy. Cohen observes that “what interested Marsh was not individuals in a crowd, but the crowd itself – the urban masses brought together randomly on subways, at the beaches and sideshows. Marsh detailed the world his figures inhabited, but left the inhabitants anonymous.â€9

One historical context for Marsh’s pictures is the preoccupation with the crowd that accompanied the rise of democracy but flourished especially during the Depression. Late nineteenth-century works like Matthew Arnold’s Culture and Anarchy and Gustave Le Bon’s The Crowd reflected a deep distrust of collective action, whether organized or spontaneous. To alarmed observers the crowd seemed to have a mind of its own, different from the individuals who took part in it. It could be transformed into a mob, irrational or anarchic, prone to violence; it could also be easily manipulated. Conservative social critics lived in fear of revolution; they denounced the leveling effects of mass culture. Between the wars these fears were exacerbated by the coming-to-power of totalitarian populist movements such as Communism and Fascism but also by the new mass media, which were quickly mobilized for advertising and propaganda. In 1930 the Spanish philosopher Jose Ortega y Gasset published an influential diatribe against what he called “the revolt of the masses,†which he castigated as an assault on reason and a descent into barbarism.

Some thirties artists like Nathanael West shared these fears. King Vidor’s classic 1928 film The Crowd evoked the urban crowd at Coney Island and elsewhere, but decried the anonymity and loss of identity in a world of strangers. But within a short time, common problems soon came to supersede the travail of individuals and families. For radicals facing what seemed like an apocalyptic social crisis, it seemed an indulgence to concentrate on psychology, introspection, or personal relationships. As they saw it, the Depression had confounded the old dreams of success or personal fulfilment. Instead they grew interested in the common man as collective man: the urban crowds that Whitman had once celebrated as the symbol of democracy; the chorus girls in their precision routines at Radio City or in Busby Berkeley’s musicals; the masses at a political rally or the fans at a movie premiere; the destitute men or women on bread lines, in hobo jungles and Hoovervilles; the trekking migrants who had lost their homes and jobs. Men in groups, women in lock step, common suffering and collective enjoyment, this was seen as the new reality.

Marsh’s instinctive affinity for the crowd embraced both the beach and the bread line, the gawking male spectators at a burlesque show and the rush of humanity on the city streets or in subway stations. Though he disclaimed any interest in politics, one of his best known images was a 1932 engraving, Bread Line – No One Has Starved, which alludes to an unfortunate (and inaccurate) phrase by Herbert Hoover that, for many, epitomized his insensitivity to the plight of ordinary Americans. From one side we see a friezelike column of men squeezed together closely, like the folds of an accordion, reflecting the tight fix they’re actually in. There’s no space above or below them; their overcoats and baggy trousers conceal their bodies; their hats obscure parts of their faces, which are expressionless. Their individuality is lost in the crowd but also in their larger social predicament, which leaves them no space, no outlet. They seem at once static and entrapped, standing on line but going nowhere.

Marsh’s instinctive affinity for the crowd embraced both the beach and the bread line, the gawking male spectators at a burlesque show and the rush of humanity on the city streets or in subway stations. Though he disclaimed any interest in politics, one of his best known images was a 1932 engraving, Bread Line – No One Has Starved, which alludes to an unfortunate (and inaccurate) phrase by Herbert Hoover that, for many, epitomized his insensitivity to the plight of ordinary Americans. From one side we see a friezelike column of men squeezed together closely, like the folds of an accordion, reflecting the tight fix they’re actually in. There’s no space above or below them; their overcoats and baggy trousers conceal their bodies; their hats obscure parts of their faces, which are expressionless. Their individuality is lost in the crowd but also in their larger social predicament, which leaves them no space, no outlet. They seem at once static and entrapped, standing on line but going nowhere.

As a Depression image this is memorable, yet Marsh’s crowds exposing their bodies at the beach or promenading vigorously through the New York streets have no more identity than these luckless men. Showing off their breasts, buttocks, or muscles, they’re bursting with vitality but remain broadly generic specimens of humanity, physical types. Only their bodies are sharply different, unlike the men on the bread line. Their blank faces, little more than caricatures, contrast with their physical presence and tell us almost nothing about them. Even in pairs or small groups – lovers, friends – Marsh’s subjects scarcely relate to each other except as interlocking bodies, displaying not physical intimacy but the body as vehicle of performance, as with the gymnasts in human pyramids doing their stunts on the beach.

The anonymity of Edward Hopper’s people, who seem less individualized than his houses, speaks to us of loneliness and isolation, but this is rarely thrust of Marsh’s work. He comes closest to Hopper in a painting like Why Not Use the “L� (1930), where the woman on the right is staring off into space, a disheveled man lies asleep, sprawling near her, and the woman on the left stands aside behind a barrier, reading a newspaper. They’re locked in the same frame but joined only by their contrasting postures, their mutual indifference. In Subway Station (1930), instead of this lassitude, we see a crowd of bustling people all going somewhere, moving in separate trajectories through a confined underground space, the dark ceiling heavy above their heads. At the center is a man with a newspaper, evidently going nowhere. In other subway images, such as a series of 1929 engravings, pairs of people draw apart and look especially vacant, just as they do in Walker Evans’s candid subway photographs of 1938.10

But more often Marsh’s subject is not alienation but spectacle, self-display. Unlike Hopper, he relishes the anonymity of city life, the chance encounters or non-encounters in which strangers brush by each other or briefly share the same space. On the streets his striding women exude energy and purpose, as if on a runway, but rarely engage with one another. At the beach Marsh becomes a voyeur drawn to the exhibitionists, such as the muscle men doing their gymnastics, but he sees the whole beach as an exhibitionistic scene, a sea of near-nudity, more unusual then than it has become today. But in theatres, as on the beaches, his people look as though they’re playing a part, not only on the stage but in the audience or even outside the theatre. All decked out, almost in costume, they’ve come there to be seen, not simply to see.

Marsh’s theatrical scenes, such as his burlesque paintings, concentrate as much on the spectators as on the performers, and sometimes only on the spectators, as in the Daumier-like figures in Audience Burlesk (1929).11 Elsewhere, even the lovingly reproduced signage and promotional photos become part of the performance. In amusement park images such as Merry-Go-Round (1930), the customers themselves become the show, as George C. Tilyou anticipated when he created Steeplechase Park in Coney Island. He offered attractions that appealed to plucky participants as well as amused onlookers, such as the “Barrel of Fun,†a rotating cylinder that kept everyone off balance and swept them off their feet, as others watched. Tilyou turned embarrassment into a popular spectacle. According to John F. Kasson’s fine book on Coney Island, Tilyou’s competitors at Luna Park went even further in conceiving the whole park as “a gigantic stage set that engulfed visitors in new roles. . . . The lines between spectator and performer, between professional entertainer and seeker of amusement, blurred. . . .â€12

Marsh’s theatrical scenes, such as his burlesque paintings, concentrate as much on the spectators as on the performers, and sometimes only on the spectators, as in the Daumier-like figures in Audience Burlesk (1929).11 Elsewhere, even the lovingly reproduced signage and promotional photos become part of the performance. In amusement park images such as Merry-Go-Round (1930), the customers themselves become the show, as George C. Tilyou anticipated when he created Steeplechase Park in Coney Island. He offered attractions that appealed to plucky participants as well as amused onlookers, such as the “Barrel of Fun,†a rotating cylinder that kept everyone off balance and swept them off their feet, as others watched. Tilyou turned embarrassment into a popular spectacle. According to John F. Kasson’s fine book on Coney Island, Tilyou’s competitors at Luna Park went even further in conceiving the whole park as “a gigantic stage set that engulfed visitors in new roles. . . . The lines between spectator and performer, between professional entertainer and seeker of amusement, blurred. . . .â€12

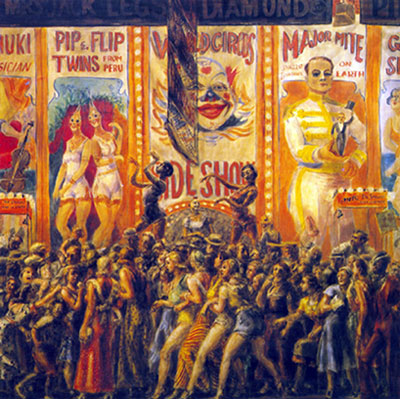

Theatrical self-projection is the overall subject of one of Marsh’s best-known paintings, Twenty Cent Movie (1936), which pictures the scene in front of a movie theatre, not inside it. This is one of Marsh’s busiest canvases. One woman, as if on stage, is strutting before the box office, another is buying a ticket, two well-dressed women wait to their left, while two men, one black, one white, strike poses as if waiting to have their picture taken. Behind them other patrons are milling about. Three huge tilted images of the movie’s stars rise above them, with elaborate signs on both sides, leaving not an inch free and forming a kind of proscenium for the action on the street. The painting blurs the lines not only between the figures in the movie and the people outside it but between stereotypical publicity images and the self-presentation of those who consume and imitate them. Walker Evans focused on the vernacular imagery of signs, photos, and storefront lettering as a little-noticed feature of everyday life; for Marsh these verbal messages and commercial images were part of the rush of impressions, the constant stimulation of living in the city. In this carnival atmosphere he limned the distant outlines of our own media-saturated environment, but he also saw the city as a stage set for ordinary people acting out in settings not so different from the amusement parks. Many of Marsh’s most complicated paintings surround the people in the foreground with a garish backdrop of oversized signs or posters. These blaring images loom over them and frame their own self-conscious poses, as in Pip & Flip (1932), Smoko, the Human Volcano (1933), and Paramount Pictures (1934), as well as a remarkable etching, Tattoo-Shave-Haircut (1932), which reveals a phantasmagoric Bowery barber shop dominated by a large sign but also dwarfed by grim girders of the El, which figures frequently in the architecture of Marsh’s street scenes. (It’s yet another proscenium but a hellish one, darkening the whole scene.) In each case our attention is divided between the backdrop and the people playing out their scenes before them, as if on an elaborate urban stage.

If, as Matthew Baigell remarks, “his characters do not live in their environments, but usually exist in front of them,â€13 this is in part because we never see the places where they live – or where they work, for that matter. We see only where they play, where they assume public postures, or when they are in transit. Like the proverbial walker in the city, reporting only what he takes in, he gives us nothing of their domestic life, their intimate emotional life, or their working life. Men drilling in the street – as in End of the Fourteenth Street Crosstown Line (1936), nicely contrasted with picketing department store employees – are the only workmen we ever encounter, people working in a public setting, enacting their own piece of street theatre.

Drawn to carnivalesque scenes and cheap amusements, Marsh is even selective in depicting their recreational life. He had little interest in the new mechanized mass culture of radio and movies, and no interest in the high-minded leisure of sports and healthy games. He gives us no equivalent of Eakins’s racing sculls or Winslow Homer’s Adirondack fishermen and Caribbean divers. His leisure scenes focus on the titillating world of burlesque, the pathos of dance marathons, the vulgar entertainment of amusement parks, the physical and occasionally sexual panorama of the beach, and the ongoing parade on busy city streets. His work is rooted in nostalgia for an older face-to-face public culture that was not mediated by technology or privatized in the home. For him these are dynamic scenes of urban flow, personal performance, and animal energy. His own art is theatrical in the same way, as in layered canvases like Twenty Cent Movie, with their distinct upstage and downstage, foreground and background, their thrust that creates almost a 3-D effect. “I like to take people and push them right out at you,†he said.14

Drawn to carnivalesque scenes and cheap amusements, Marsh is even selective in depicting their recreational life. He had little interest in the new mechanized mass culture of radio and movies, and no interest in the high-minded leisure of sports and healthy games. He gives us no equivalent of Eakins’s racing sculls or Winslow Homer’s Adirondack fishermen and Caribbean divers. His leisure scenes focus on the titillating world of burlesque, the pathos of dance marathons, the vulgar entertainment of amusement parks, the physical and occasionally sexual panorama of the beach, and the ongoing parade on busy city streets. His work is rooted in nostalgia for an older face-to-face public culture that was not mediated by technology or privatized in the home. For him these are dynamic scenes of urban flow, personal performance, and animal energy. His own art is theatrical in the same way, as in layered canvases like Twenty Cent Movie, with their distinct upstage and downstage, foreground and background, their thrust that creates almost a 3-D effect. “I like to take people and push them right out at you,†he said.14

With his privileged background at Lawrenceville and Yale, Marsh’s attraction to working-class amusements can be seen as a form of slumming. Yet as the son of two artists his upbringing was hardly circumscribed by genteel or Victorian values. Many writers and artists of the thirties were drawn out of their own orbit to report on how ordinary Americans were coping with the Depression, but Marsh remained unusual in focusing on their pleasures and diversions rather than their troubles. Their private lives interested him much less than how they briefly broke free of their lives, which was the way working-class recreations developed in the first place. Historian Kathy Peiss described how, earlier in the century, “the alluring world of urban amusements drew young women away from the ugliness of tenement life and the treadmill of work.†For them an excursion to a park or beach resort provided “a brief outdoor respite from tenement apartments, crowded neighborhoods, and busy workshops.†At Coney Island, the ultimate pleasure ground, the “beaches, boardwalk, and dancing pavilions were arenas for diversion, flirtation, and displays of style.â€15 Gradually, as America’s moral values loosened and shifted, as relations between the sexes grew less formal, these lower-class pursuits became part of the mainstream while remaining faintly disreputable. Miniature versions of Coney Island’s amusement parks took root in America’s smaller cities or traveled from town to town as carnivals and circuses, each with their own Ferris wheels, sideshows, and games of chance.

The Depression created a massive new market for “diversion, flirtation, and displays of style.†Earthy working-class pleasures and swank upper-class amusements now took on a broader social function. Just as the bubbly night-club culture of the twenties found its genius in the songs of Cole Porter or the dancing of Fred Astaire, as the back-street roots of jazz fed into the vibrant music of Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and Benny Goodman, so the vulgar culture of cabaret, burlesque, vaudeville, and Tin Pan Alley was transposed into buoyant entertainment for Depression-weary Americans seeking respite and relief. The showiness, energy, and hedonism of this culture arguably had a personal appeal for Marsh but it also coincided with the needs of the moment, the collective experience of many Americans. In his speeches and fireside chats, FDR often described how people’s lives were intertwined, how much they needed each other, since they all would eventually sink or swim together. Writers like John Steinbeck relentlessly pursued this theme of solidarity over individualism, mutual recognition rather than competition. In his own way Marsh set out to portray elements of that collective experience, partly grim, as he saw it on bread lines and on the Bowery, but also vital, sensual, and irrepressible. Rare among American artists, he saw city life itself as exhilarating, not dehumanizing, as a Whitmanesque scene that released new human energies. His engagement with the crowd was not to warn against its submersion of individuality, its threat to identity, or its collective irrationality, but to celebrate its public performance of avid curiosity, sublimated desire, and gaudy self-fashioning, which the reverses of the Depression had done much to darken and undermine.

NOTES

1. On Marsh’s work with Dos Passos’s novel, see the Afterword to Janet Galligani Casey, Dos Passos and the Ideology of the Feminine (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 176ff.

2. On the extraordinary range of leisure activities portrayed by the Impressionists, see especially Robert L. Herbert, Impressionism: Art, Leisure, and Parisian Society (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988). Many of these activities were suburban and rustic rather than urban. They represented islands of calm away from the city, not scenes from city life.

3. On the Minskys and the history of burlesque, see Karen Abbott, American Rose: A Nation Laid Bare, the Life and Times of Gypsy Rose Lee (New York: Random House, 2010). For Billy Minsky’s explanation of burlesque’s popularity in the 1930s, see p. 250. For a comprehensive overview of the portrayal of burlesque in American art, see Jennifer Munro Miller, “In the Flesh: The Representation of the Burlesque Theatre in American Art and Visual Culture†(PhD diss., University of Southern California, 2010). The seamier side of burlesque and the efforts to ban it are recorded in Rachel Shteir, Striptease: The Untold History of the Girlie Show (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004).

4. Susan Currell, The March of Spare Time: The Problem and Promise of Leisure in the Great Depression (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005).

5. A delectable survey of these fads and fashions remains Frederick Lewis Allen, Since Yesterday: The 1930s in America, September 3, 1929Â-September 3, 1939 (1940; New York: Harper & Row, 1972), especially the chapter “A Change of Climate,†105Â-130. But see also Harvey Green, The Uncertainty of Everyday Life, 1915Â-1945 (New York: HarperCollins, 1992), 187Â-237.

6. On the growth and transformation of leisure activities between the late nineteenth century and the 1920s, see especially Lewis Erenberg, Steppin’ Out: New York Nightlife and the Transformation of American Culture, 1890Â-1930 (1978; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981); Kathy Peiss, Cheap Amusements: Working Women and Leisure in TurnÂofÂthe Century New York (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1986); and David Nasaw, Going Out: The Rise and Fall of Public Amusements (1993; Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999).

7. Lloyd Goodrich, “Introduction,†Norman Sasowsky, The Prints of Reginald Marsh (New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1976), 12.

8. “The total effect is one of continually flickering vibration from left to right and from top to bottom, which forces our eyes to move as rapidly as the figures themselves. The nervous tensions that Marsh’s strokes elicit are resolved only when the viewer turns away from the painting.†Matthew Baigell, The American Scene: American Painting of the 1930’s (New York: Praeger, 1974). Baigell makes similar points about his habitual use of shifting and diluted colors and odd, disorienting perspectives, contributing to the instability of the image.

9. Marilyn Cohen, Reginald Marsh’s New York: Paintings, Drawings, Prints and Photographs (New York: Dover, 1983), 12.

10. Sasowsky, 118Â-120.

11. Sasowsky, 127.

12. John F. Kasson, Amusing the Million: Coney Island at the Turn of the Century (New York: Hill & Wang, 1978), 65.

13. Baigell, 146.

14. Quoted by Cohen, 41.

15. Peiss, 57, 117, 115.